Last time we checked out the views from the Bunda Cliffs on the Great Australian Bight and had a good look around Koonalda Station.

Koonalda Cave – What Lies Beneath The Surface?

The Nullarbor is basically a huge slab of limestone. In places, the limestone has dissolved to form caves. Some of these caves connect with the ocean to form blowholes, while others contain drinkable water.

Koonalda Cave lies a few kilometres north of Koonalda Station homestead. Measuring 85 metres in diameter, this is a seriously large hole in the ground. The only indication of the cave is a fence. You won’t see the sinkhole until you’re right on top of it.

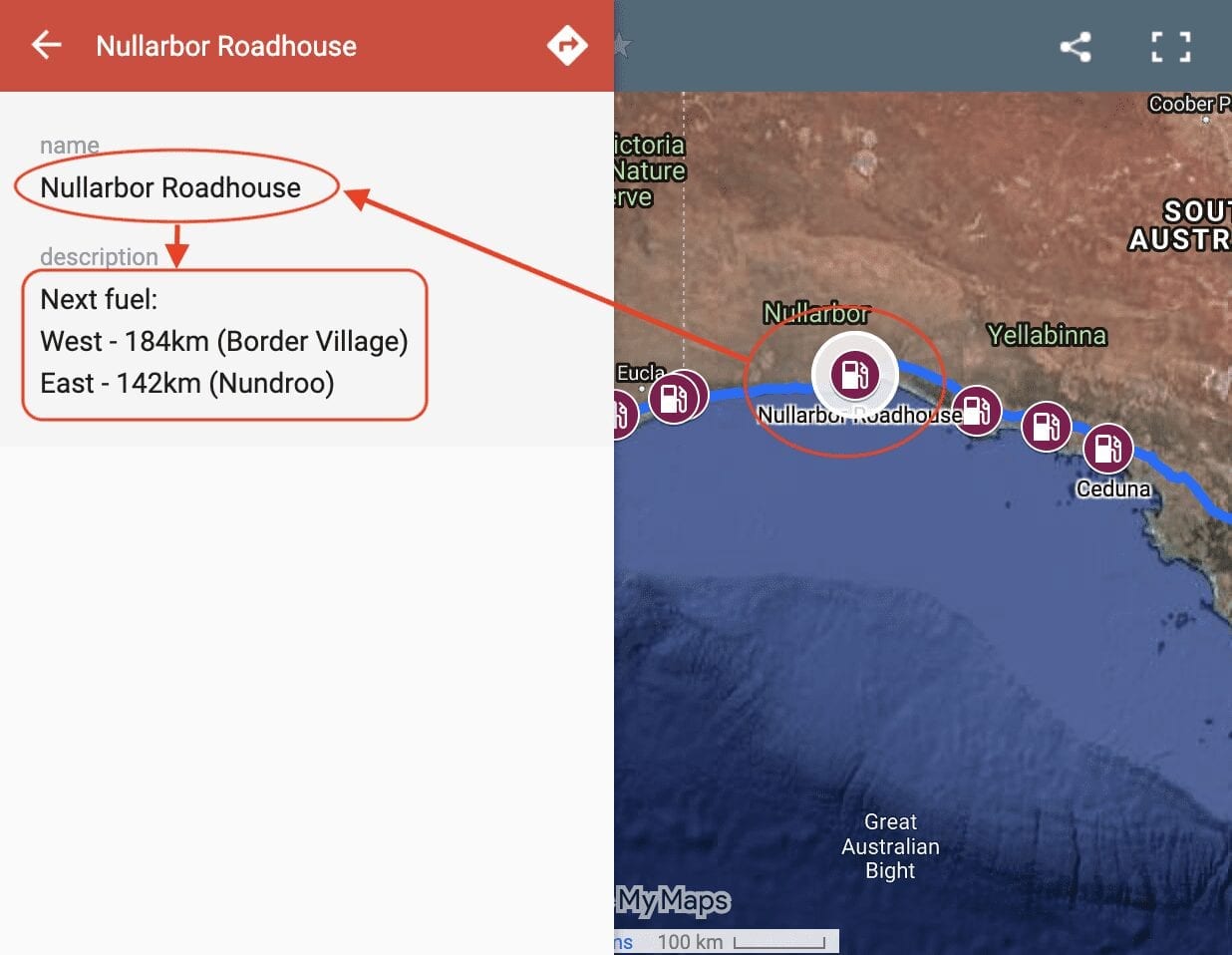

Fuel Stops

So where you can get fuel on the Nullarbor? Our Interactive Map of fuel stops across the Nullarbor will give you all the info you need.

The sides drop vertically for about 20 metres, with some parts undercut. From here, a steep slope leads down to the floor at about 70m depth. At this point, the cave apparently opens into a giant 60 x 90 metre cavern. A domed roof towers about 40 metres overhead.

More Questions Than Answers

Apparently, various caves branch off from the main chamber. Venturing deep underground in the 1950s, archeologist Dr Alexander Gallus discovered Indigenous art dating back 22,000 years.

Long lines of finger painting etched in the soft walls presented archeologists with a mysterious puzzle:

- How were they created, given there’s no natural light?

- What do they mean, why are they there?

- What’s their cultural significance?

- Do they perhaps point out where the flint mines are?

When archeologists explored Koonalda Cave in the mid 1950s, they thought Aboriginals had occupied Australia for “only” 8,700 years.

This discovery turned accepted knowledge on its head.

The local Mirning people used the cave to mine flint, and as a source of drinking water. Being hard and durable, flint was ideal for stone tools. Remember, this was happening around 22,000 years ago.

More recently, the Mirning People used Koonalda Cave as an initiation site. Modern cavers use ropes and ladders to descend the cave. But the Indigenous people have a pathway down the sheer walls… they have no need of ladders.

The Plain Lives and Breathes

Indigenous people are afraid of the Nullarbor… or more accurately, afraid of Ganba the magic snake. They believe Ganba lives below the surface. He comes to the surface and thrashes around, causing dust storms. He drinks all the rainwater – as soon as it rains, the water disappears. He ate all the trees. He eats people… many people have entered the Nullarbor, never to return.

It’s a great explanation of what these people witnessed. Think about it – there are many sinkholes descending into caves. A change in air pressure at the surface causes the air to either rush in or out of the holes. These small holes in the plain appear to be breathing. Even worse, the accompanying sounds can send chills down your spine.

Ganba’s down there, it all makes sense.

Therefore the Indigenous people tended to live along the coast or in the desert country, and not venture far onto the plain. Near the coast, fresh water was found in soaks behind sand dunes. Given Ganba was lurking, Koonalda Cave was used as an initiation site – the ultimate test of manhood.

Saving Koonalda Cave From Vandals

Koonalda Cave has an unimaginably long and rich history. And it’s basically in the middle of nowhere. So you’d assume people would respect it, right?

Apparently not.

In 2022, an unknown group of morons dug under an access gate, climbed down into the cave, and scrawled graffiti over a section of art. I’m not going to tell you what they wrote, I’m not giving them that recognition.

We’re talking about trashing perfectly preserved finger paintings… finger paintings created 22,000 years ago. To give you a reference point in time, the first pyramid in Egypt was built around 4,500 years ago.

In 2023, the federal government announced funding for improved fencing and security cameras. While this is a welcome announcement, the fact we even need this added security is beyond sad.

What is it about the Indigenous culture that so many of us are afraid of?

Australia has the oldest continuous culture in the world by a long shot, yet many of us can’t seem to accept this fact.

We’re awe-inspired by man-made structures that are only a couple of thousand years old at the most… the pyramids, York cathedral, and so on. And they’re impressive, for sure.

But Australia has man-made creations an order of magnitude older than those things we revere overseas:

- Finger paintings and mining at Koonalda Caves over 22,000 years old. Damaged by graffiti.

- More than one million petroglyphs over 50,000 years old near Karratha in WA. Under threat from vandals, iron ore mining, and emissions from a nearby LNG plant.

- Juukan Cave in WA which had artefacts proving over 46,000 years of continuous occupation. Blown up and completely destroyed by Rio Tinto…

…to name but three.

Yet many of us don’t seem to care.

If an ancient art site was vandalised in Europe, there’d be worldwide uproar. And rightly so.

But I’m guessing this is probably the first you’ve even heard of the 2022 vandalism at Koonalda Cave.

It’s high time we grew up as a nation. It’s time we showed some collective pride in the incredibly rich and diverse cultures that have developed in Australia for at least 65,000 years.

Next time: Reaching the WA border – The Old Eyre Highway and Border Village.

This section of the Nullarbor trip is on Mirning Country.

Looking for more information on the Nullarbor? Then go here.

Get your BONUS Guide:

Download “Nullarbor East to West – A Traveller’s Guide”

…at our FREE RESOURCES Page!

Any questions or comments? Go to the Comments below or join us on Pinterest, Facebook or YouTube.

Any errors or omissions are mine alone.

Do travellers have access to the cave site. My wife & I travelled the Nullabor many years ago and although we researched a number of sites we found there was no access for visitors

Russel Mc Kenzie

Hi Russel,

No, there’s no access to the public, however you can view it from the top. It’s an impressive sight and well worth a visit.

Cheers, Andrew