Note: This article contains an affiliate link to Apple. If you click through and make a purchase, we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Charles Sturt had an idea. He was convinced an inland sea covered much of inland Australia.

To Sturt, everything pointed to it. The rivers flowing west from the Great Dividing Ranges and even the regular sightings of waterbirds flying North-West between Melbourne and Adelaide.

So in 1845 he set out from Adelaide to find this mythical inland sea. He followed the Murray then the Darling, finally striking out North-West into unknown country.

And that’s how he ended up in the Corner Country in New South Wales… complete with a boat and sailors!

Sturt was no fool though. He was an incredibly capable person, able to make critical decisions when needed, respected by his men, respectful of Indigenous people, and unwaveringly focussed on a successful expedition.

One of Sturt’s expedition depots was Fort Grey, on the southern reaches of Lake Pinaroo.

Fort Grey Campground

Fort Grey Campground in Sturt National Park is a bit easier to get to these days. It’s just off the road along the Tibooburra – Cameron Corner Road. The campground is about 100km from Tibooburra and 30km from Cameron Corner, and just off the road.

Remember though, it’s still remote country and you have to be entirely self-sufficient.

Once you arrive at the campground, National Parks have spoilt you. Two lots of gas BBQs under shelters and two separate toilet blocks make camping a bit easier. And there’s plenty of room to set up and have some space.

Like many National Park campgrounds, fires are not permitted. There’s a couple of reasons. One because this is arid zone country with cold nights and often warm, windy days. It’s easy for a campfire to spring back to life mid-morning, once the air heats up and the wind starts.

The second reason is that all dead timber is precious in this country. It’s a critical part of the dune country life cycle. Termites eat eat timber, small reptiles eat termites, tiny marsupials eat insects and small reptiles, kites and eagles eat the marsupials and so on.

Plus the fallen timber plays a vital role in holding the fragile sands together and providing ground cover.

And as you drive in, you can’t help but notice a giant quoll at the entrance. And yes, it’s been unofficially christened the big Quoll! This is one of three magnificent wire sculptures on the drive between here and Cameron Corner.

Behind the Big Quoll is an excellent Visitor Information shelter. It has a wealth of information about the region, including a whole lot of interesting facts about Lake Pinaroo and the wildlife it supports.

Lake Pinaroo Walk

When you stay at Fort Grey Campground, the Lake Pinaroo walk is a must-do walk. It starts at the eastern end of the campground and does a clockwise loop past the Old Fort Grey homestead, across the lake past an Aboriginal cooking hearth, onto an old well, past the remains of a timber brush fence then back over sand dunes to the campground.

Just after the well, you can also strike out across the lake to Sturt’s campsite. This is a one way route. Sturt named his depot Fort Grey and used this as a base to explore to the west and north.

Fort Grey was named after Governor Grey, governor of South Australia at the time.

NSW National Parks have done a remarkable job installing interpretive signage in many spots along the walk. We always enjoy these signs because it brings the place to life.

Let’s have look at the highlights of this walk in more detail.

Lake Pinaroo

This ephemeral lake rarely fills. The huge rains of 1956 and 1974 were the standout flood events which had water lapping near the top of the dunes. And when you look at where the water has to come from, then you begin to understand why a filling event is so rare.

The Lake was listed as a Ramsar site of significance in 1996. For more information, go here.

If you drive out from Tibooburra, you’ll pass through the Grey Range. You climb up then sit on top of a plateau. The water from this plateau runs west and loosely follows Fromes Creek. As it flows west, Fromes Creek spills into the massive Frome Swamp. You run beside this for a while as you come out from Tibooburra.

Once Frome Swamp is full, the water spills over to the west into Fromes Creek and into finally into Lake Pinaroo.

We’re talking over 40km from Grey Range to Lake Pinaroo across some seriously arid country. Little wonder you need huge rains to saturate the ground, then fill Frome Swamp then Lake Pinaroo. Considering Tibooburra’s annual rainfall is about 200mm, you can understand why this is such a rare occurrence.

In March 2021, just such an event happened. Between 100mm and 140mm of rain in less than 2 days, across a wide band. Combined with earlier rains which had already saturated the ground, Lake Pinaroo filled again.

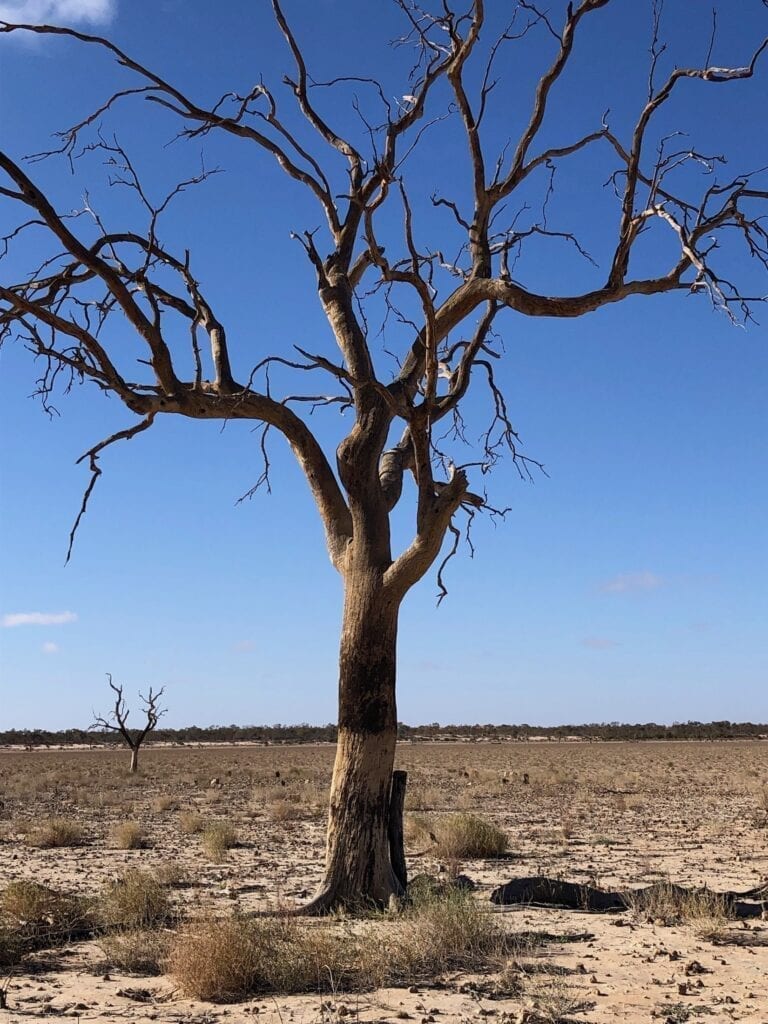

Lake Pinaroo has a few standout features. Your first glimpse is from the top of a red sand dune through surprisingly dense coolabah trees. Its light grey colour is a stark contrast to the red sand dunes.

Why All The Dead Trees?

Then as you get closer, you’ll notice thousands of dead trees on the flat lake bed. These trees drowned when their roots were covered with water for over 7 years in the 1970s. In fact, some of them still bear witness marks on their trunks of the flood level way up their trunks. Standing in the lake bed, it’s hard to imagine this much water being here.

And what a sight it would be. Sturt National Park comes alive… Lake Pinaroo would be full of life, with millions of waterbirds making the most of this windfall event.

But why is the lake bed and indeed some of low rises within the lake almost white in colour? To answer this, you have to look at where all the sand came from.

During the last ice age, the inland sea retreated and left a vast swathe of sand and sediment behind. Low rainfall and ever-present winds blew huge amounts of sand from the Strzelecki Desert into this area. As it aged, the iron in the sand oxidised to form the distinctive red colouring of the outback. In general terms, the darker the red sand, the older it is.

Now when a region like Lake Pinaroo floods, you’re talking a long term flood. For example, the lake took about seven years to dry out after the 1974 event. The water actually leeches the iron oxide out of the sand and it re-emerges as white in colour. So you get this pocket of white sand in among the red sand dunes.

Of course, pale clay from the jump-up country also contributes. As you walk onto the lake, you’re heading towards the mouth of Fromes Creek. You’ll notice the clay gradually overwhelming the sand. This is because the clay is deposited from the creek mouth and more of it settles closer to the creek mouth.

Keep an eye out for the distinctive lines of coolabahs along the shoreline. Coolabahs seed once a year. The lake took about seven years to dry out after the 1974 flood. You can see where each shoreline was when the coolabahs seeded. The lines of younger trees are quite obvious if you look carefully.

Old Fort Grey Homestead

Just as you arrive at the shoreline of Lake Pinaroo, there’s an old windmill on the left. Wander over and have a look around. High up on the sand dune near the windmill is a sign showing the high mark of the 1974 flood.

Lower down the dune you’ll see a jumble of stone. This was the old homestead. It was abandoned after the 1956 flood, when the owners realised the house and surrounding infrastructure was in fact flood-prone.

Apparently the house stood until waves from the 1974 flood undermined the house and it collapsed.

Look around. You’ll find remnants of old yards and fences. And take a minute to reflect on how isolated this station was. While the people who built this house were wise enough to choose a reasonably protected site, they could never have imagined it would one day disappear under water!

Cooking Hearth

A little way onto the lake bed you come across a large scattering of small stones. These formed the base of a cooking hearth used by Aboriginal people. They were the heat beads under the fire and shattered due to the heat.

I haven’t been able to find out any detail about its age. Much of this history has been lost after families were rounded up and trucked to a mission in Brewarrina.

It’s curious how far this hearth is from the shoreline and therefore its lack of protection from the elements. I guess the lake bed may have been more heavily vegetated back then. Who knows.

A Well… A Long Way From Anywhere

A couple of kilometres onto the lake is the remnants of a well. A rusty steam boiler still sits there, looking pretty forlorn and lonely out there.

It once ran a walking beam pump, bringing water to the surface with each upstroke. The well was used to water stock, but was abandoned after being flooded one too many times.

Around the well is an old bore casing which would have had a windmill over it, remnants of a tank or trough and the piers of a crutching shed. Working sheep out on this lake bed would have been a hot, shadeless job in the hotter months!

Sturt’s Tree, Fort Grey

Just past the well, you’ll come to the halfway mark. Go right and make your way back to the campground or go straight on to Sturt’s Tree. This adds another 3km to your walk, but it’s worth doing.

We did this in early winter. The cold south-westerly wind did its best to cut us in half as we trudged headlong into the wind.

And remember how I was saying the clay dominates the lake bed as you move towards the mouth of Fromes Creek? Well, Sturt’s Tree happens to be quite close to the creek mouth. So the ground softened and the walk was more difficult… like walking through soft sand in places.

If you’d like to learn more about Sturt’s inland expedition, I highly recommend “Sturt’s Desert Drama” by Ivan Rudolph. It’s a fascinating read.

- For Paperback version ➜ click here.

- For Kindle version ➜ click here.

- For Apple iBooks version ➜ click here.

Quite close to Sturt’s Tree you pass a waterhole. Waterholes like this are the last to dry up in the lake, so provided invaluable water sources for the First Nations People. Sturt actually noted the huts built in this very area.

I wonder what the Aboriginal people thought when 17 white people turned up with horses, bullocks drays, carts, sheep, sheep dogs and a boat! Not only that, they then built a fortification and the strange animals drank much of their precious water.

We sat there for a while and imagined this spectacle arriving over a sand dune. The First Nations People must have been gobsmacked. What were these strange creatures? Why are they taking all our water?

It would be like you or me sitting out on the front deck when an alien spaceship lobs up the road, lands in your front garden and disgorges a bunch of weird creatures. Then they won’t leave! How do you tell them to bugger off?

Anyway… Sturt’s Tree has been propped up by steel posts. The tree drowned in the 1956 floods, so the steel posts prevent it from splitting in half and falling over. You can clearly see the blaze on the western side made by Sturt or his surgeon John Browne in 1844 and another blaze on the eastern side, made by a surveyor in the 1920s.

Is this the site of the Fort Grey stockade or not?

That question will probably never be answered. We know it was in the vicinity, but it’s impossible to tell if Sturt’s Tree is the actual site. Large floods and land degradation by rabbit plagues and over-grazing have changed the landscape, making it almost impossible to compare sketches done then with what’s in front of us now.

Sturt pushed out from here, “discovering” Cooper Creek. But he never found his inland sea. Little did he realise that he was camped in an inland sea of sorts.

It just wasn’t permanent.

I’m surprised Sturt, his assistant Poole or a young John McDouall Stuart couldn’t read the country better. All the signs are there that this lake fills way beyond the level you’d think was possible. Maybe it hadn’t filled for a long time beforehand. Or maybe they were too fixated on finding their inland sea.

Dairies from the Sturt expedition describe numerous “box” (coolibah) trees providing shade and shelter. So perhaps the lake hadn’t filled for many years prior to Sturt’s visit.

Our return trip back to the loop track was easier, with the wind now threatening to shred our backs. At least we had a tail wind!

A Difficult Way To Build A Fence

Back onto the loop road and you soon come to wooden fence made from coolabah trees. It’s a few hundred metres long and looks like hard work!

The fencers would have first sunk sets of two vertical posts side by side, about 300mm apart. Then they cut down mulga or coolabah trees and laid them horizontally, slotting them in between the sets of vertical posts.

In this manner, they formed the wooden fence you can see the remnants of now. This would have been an incredibly labour-intensive way of building a fence. But the pastoralists were simply using the resources they had available.

The Final Act

Pretty soon you’re back in the sand dune country, in among the red dunes. The contrast between here and the lake bed is quite stark. Not only has the sand turned a deep red colour again, but you’re actually quite protected.

Surprisingly, the trees are quite thick in between the dunes. We saw some green patches where the water lies after rain. So obviously the trees are tapping into this ground water.

Up and over the final dune and Fort Grey campground is in sight again. You’ve made it!

Endless Cycles

Lake Pinaroo has likely been filling and evaporating for thousands of years. The hot dry climate means it’s empty most of the time. But when it fills, the Lake Pinaroo is a spectacular sight.

Diary entries from men on the Sturt expedition are fascinating. Brock writes of “a creek passing some distance into the flat, and here terminating, the waters when the creek is full passing over, forming a kind of lagoon”.

Sturt writes, “Immediately in front of the tents there was a broad sheet of water shaded by gum-trees, and the low land between this and the sand hills was also chequered with them (trees)… The open grassy field or plain stood full in view”.

Perhaps Sturt’s expedition chanced upon Lake Pinaroo when the lake had almost dried out, after a big rain event. As these two photos show, the lake can look totally different depending on the seasons.

Add more coolabahs and it’s similar to Brock and Sturt’s descriptions. Had Sturt been here a year earlier, he may have encountered a vast lake. That would have been a small reward for his efforts.

Sturt pushed himself beyond his limits, yet somehow survived. By the time he left Fort Grey and returned south, Sturt knew the inland sea didn’t exist. But he kept pushing himself, exploring vast areas of this region in extreme heat, often with little food or water.

There’s a small part of me that wishes he’d seen Lake Pinaroo with water in it. After all his super-human efforts, he deserved a refreshing swim…

Lake Pinaroo and Sturt National Park are on Wongkumara and Maljangata country.

Looking for more NSW Corner Country destinations? Then go here.

Get your Traveller’s Guides

… and a whole lot more at our FREE RESOURCES Page!

Any questions or comments? Go to the Comments below or join us on Pinterest, Facebook or YouTube.

Any errors or omissions are mine alone.

Thanks for the very interesting observations and thoughts about this area.

Really enjoyed reading it and also watching your video.

Thanks Martin! Cheers, Andrew