Note: Wild Deserts is a restricted area, not open to the public. We were invited to Wild Deserts as volunteers.

It’s April… autumn in Australia. You’re driving through the desert country of far North-West New South Wales, between Tibooburra and Cameron Corner.

This is Corner Country.

Two years of record dry seasons and record temperatures have baked this country. With only 38mm of rain for the entire year in 2018, the Corner Country is struggling big time.

Heat blasts in through the windscreen and the air conditioning is cranking. Looking around, all you see are dying trees, bare ground and blazing hot red sand dunes. You pull up for a break and when you get out, the heat hits like someone just opened a furnace door. You scurry to the shade of your vehicle, crouched down against a tyre.

How could anything possibly survive out here?

Well, you’d be surprised. Nature’s a bit smarter than us. The creatures living in this country not only survive, they thrive. Australian marsupials and reptiles have adapted to our harsh climate over many thousands of years. Unfortunately, humans have changed their environment faster than they can adapt.

And this is where Wild Deserts come into the picture.

A Sanctuary Of Sorts

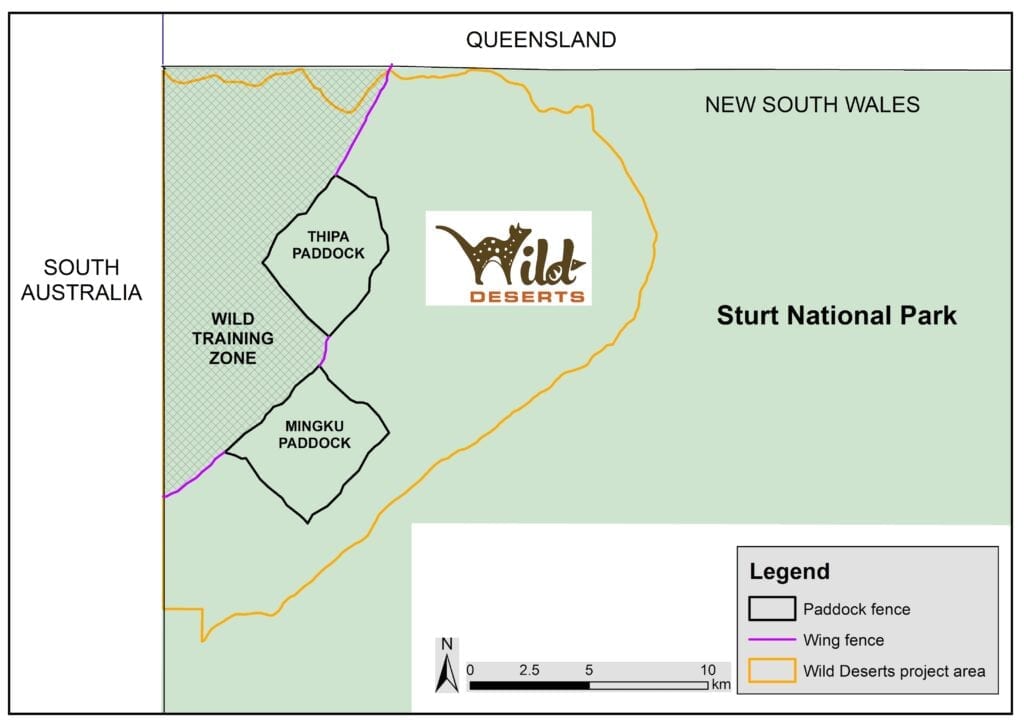

We explained what Wild Deserts is and what it hopes to achieve here. Suffice to say, it’s a breeding ground, a “safe area” in which native creatures that once lived in this area can be reintroduced. Native creatures can establish colonies without the threat of feral predators and invasive species like rabbits and kangaroos.

Now controlled areas are ideal for conducting research, if set up correctly. This is especially true for Wild Deserts. Firstly, it’s new. So ecologists can get a baseline of environmental conditions, a before and after if you like.

Secondly, it has different zones designed to achieve different outcomes. And thirdly, it sits beside the dingo fence.

This enables ecologists to compare the dingo-free Wild Deserts environment with the South Australian environment on the other side of the fence… one that still has the dingo as its apex predator.

Down the track, other species will be reintroduced to Wild Deserts. These creatures have been extinct in the Corner Country for over 100 years. The focus is on:

- Bilbies,

- Burrowing bettongs,

- Stick-nest rats,

- Western barred bandicoots,

- Golden bandicoots,

- Western quolls, and

- Crest-tailed mulgaras.

If you want to see what these what these cute Australian marsupials look like, go here to see them.

Right now though, Wild Deserts staff are waiting for rain. In the meantime, tiny mammals and a wealth of reptiles are busy re-populating the area… even in such desperately dry times.

But there’s not much point doing all this work if you don’t know what’s living and growing there now. Cue the annual Ecological Survey.

Rolling In

Peta and I volunteered for the Wild Deserts annual Ecological Survey. We had no idea what was involved or what to expect. It just somehow sounded interesting.

We arrived at Fort Grey Homestead in early April during a late burst of summer. Fort Grey’s about 100 km from Tibooburra and 30km from Cameron Corner. It was a welcome sight after the rough corrugated road.

The homestead is about 100m off the road, and surrounded by large gums and outbuildings. The gums were a surprise. We were expecting nothing more than a few sparse mulga trees.

As we drove in, we noticed a 4WD parked just off to the left. It faced a tiny soak, created by the grey water outlet from the homestead. A young bloke was sitting in the passengers seat and the ute was copping the full blast of the early afternoon sun. Hmmm, that’s different.

Welcome to Wild Deserts!

It turns out Simon is an honours student. He has a passion for birds and was conducting a count of species coming in to drink from the soak. He was using the ute as a kind of bird hide. I reckon I’d have found some shade though. Sitting in a boiling hot ute for 3 hours straight isn’t my idea of fun!

We met Bec and Reece, the couple who live at Fort Grey and turn all the Wild Desert dreams into reality. They have a baby daughter Isla, who managed to steal everyone’s hearts pretty quickly.

Rounding out the family unit is Peggy, a highly intelligent sheep dog used as a rabbiting dog. She will no doubt play other vital roles as a detection dog in the future.

Reece pointed us to a shady spot under a large gum tree and we set up camp.

Then we met Vicki. She was catering this week and soon became renowned for her amazingly delicious dinners and her famous “Vicki bikkies”… an endless supply of delicious homemade biscuits and muffins.

Vicki was an interesting person. She has tried her hand at just about everything… contract mustering, cooking for stock camps, fencing and so on. She’s currently helping out her parents, hand feeding stock in Northern Victoria. After spending several years around Packsaddle, Vicki has bought a house at Tibooburra. She would love to settle there and concentrate on being an artist.

Meeting The Crew

As the afternoon wore on, more people rolled in and set up. Students, ecologists, all sorts of people from a variety of fields. We had reptile experts, bird experts, plant experts, spider experts, fungus experts, invertebrate experts. You name it, they were there.

And then there was us.

Peta and I have both worked with uni people in our dark distant past, Peta more so than me. Our experience had been primarily with academics, people often slightly detached from the real world and often more than just a little eccentric.

So we were pleasantly surprised to discover these people at Wild Deserts were down to earth, enthusiastic and practical. Above all, they were an inspiring and passionate bunch.

This was going to be fun!

An afternoon induction and introductions over dinner gave us some idea of what we’d be doing in the coming week. Most of the others had done this type of work before, so Peta and I were about to embark on a steep learning curve.

Oh and one thing we didn’t expect. We were the oldest people there, with the possible exception of John Read… sorry John! In fact some of our team mates were actually younger than our own kids! This took a while come to terms with.

It’s a strange feeling being the oldies of the bunch!

An Early Start

With the first two days forecast to be in the mid-thirties, an early start was in order. Peta and I were up before 5am, keen to get started. After a hearty breakfast (thanks Vicki!) we packed lunch and filled our bags with as many water bottles as we could fit.

We split into teams. Peta was with John Read on the first day. John is a kind of perpetual motion machine and his team were in for a long, hot day.

I jumped in with Tom Hunt, Steph and Chloe. We made for the SA/NSW border, setting up pitfall traps and invertebrate traps as we went.

It’s hard work. You spend much of the day on your hands and knees, digging out sand on the dunes or digging into rock-hard clay on the swales. We spent the first day setting up traps and were pretty relieved when the last one was done.

Back to the homestead for a well-earned shower and some relief for all the sore muscles we’d forgotten we actually had.

After day one, we had gelled into a cohesive bunch. Everyone did their bit and we all got on famously. Peta and I were beginning to realise just how knowledgeable our co-workers were. Several have had incredible experiences in arid zone lands. People like John, Bec, Reece and Tom H have an extraordinarily broad knowledge of all aspects of arid zone ecology.

While each has their specialty, we were blown away by their knowledge, passion and willingness to pass on their knowledge to novices like us.

What also struck us was the incredible amount of knowledge everyone else had… Simon with birds (thanks for showing us the beautiful Bourke’s Parrot, Simon), Tom B with snakes and lizards, Chloe with spiders, Lucy with bees as just a few examples.

We appreciated their patience in teaching us, in passing on just a tiny chunk of their extensive knowledge. Thanks everyone, we’ll never look at a sand dune the same way again!

Up And Into It Again

Day two dawned. Well actually we were up 2 hours before dawn, but that’s okay.

Anyway, day two dawned and we all realised Chloe is definitely not a morning person. How someone can awaken, dress, eat breakfast and pack lunch with their eyes closed I’ll never know. Regardless, she was ready in time every single morning… a massive effort for a night owl.

Day two was a mix of setting up traps and checking the ones we’d set up the day before. After day two, all teams settled into a routine of checking traps and then completing other vital work like vegetation surveys and belt transects.

And the best part? Checking the pitfall traps. What would we find?

The Cutest Creatures

You might be surprised to learn the desert comes alive at night, especially warm nights. We caught lots of lizards, small marsupials and even a curl snake!

When I first saw a pitfall trap set up, I thought, “Surely lizards and marsupials don’t just fall into a hole”. Well, that’s exactly what they do.

They run or slither or hop along the low fence, following it along, trying to figure out how to get past or around it. Before they realise what’s happened, the ground suddenly disappears and they drop into a hole.

Apparently there’s also an element of curiosity. The fence is something new, so they just have to explore it. This is why the number of catches drops off after the first couple of nights.

Peta and I were really keen to see a dusky hopping mouse.

You see, we had seen a curious set of tracks on a sand dune just off the Strzelecki Track a few days earlier. We described the tracks to Reece and Bec, who said they were dusky hopping mouse tracks.

Somehow Peta and I decided they were pretty cute, so we really wanted to see one in real life. As luck would have it, Tom Hunt’s team caught one on the very last day and showed it to us. It turns out they are indeed ridiculously cute.

We decided to hopping-mouse-nap her and keep her as a travelling companion in our truck. I wish!

Personally, I was fascinated by the variety of lizards. I said earlier that Vicki is an artist among other things. She commented on how the patterns on the lizards remind her so much of Aboriginal art. She could see exactly where Aboriginal people found their inspiration for the colours and patterns they use in their art.

And she’s spot on.

When you see these reptiles close up, they are so intricately patterned. Each species can have an entirely different pattern to a genetically related species, or they may look identical with just one tiny difference in their markings.

Even in the driest of dry conditions, these creatures are breeding and thriving in this arid country.

Species like the central netted dragon really have the cards stacked against them. Apparently 90% of the males survive for just 12 months. So they must breed every year, even in record dry times like these. Otherwise they’ll die out. No pressure boys…

Why have they evolved this way? The answer’s way beyond my knowledge. That’s a question for an arid zone ecologist!

The Weird And The Wonderful

Perhaps the weirdest creature though is the Lerista labialis. It looks like a skink but only has two back legs. They slither like a snake through the sand until the going gets a bit tough. Then they use their back legs for more traction. A bit like a limited slip diff really…

You might be wondering how reptiles are surviving at all, considering the severe drought. Well, most of them live on ants and termites. So they’re always assured of a feed, at least while the vegetation is still there.

The best part of pitfall trapping is releasing the reptiles and mammals after they’ve been recorded and measured. Most of these creatures are pretty cute!

We discovered the lizards have distinct survival mechanisms. Some play dead when they’re captured, others stay completely still, only to execute a high-speed take-off whenever an opportunity arises, while others just keep wriggling, hoping they might break free.

The tessellated gecko has a clever disguise. It curls up into a kind of knot and looks exactly like kangaroo poo. It plays dead and doesn’t move if you pick it up.

So when you release lizards, they’ll either scurry off in a blaze of sand or lie motionless on your hand until you place them gently beside a hole or burrow.

The geckos are without doubt the cutest. Their enormous eyes and knobbly markings make them look like miniature ET’s. The geckos are closely followed by the dragons on the cuteness scale. These cheeky little fellas absolutely motor across the sand.

By now, you might be getting an inkling as to why we enjoyed our time at Wild Deserts so much. All these new creatures we’d never heard of let alone seen, every single day jam-packed with learning new things and a week with a bunch of great people. It really doesn’t get much better than that!

Positive Results

And what did we discover? Anything new or exciting?

Well, last year they caught a Mulgara. This is one of the locally extinct species Wild Deserts is planning to reintroduce. It was an exciting find, as it showed Mulgaras were able to repopulate this area given the right conditions.

This year, one team found a stripe-faced dunnart. This vulnerable species hasn’t been caught in Wild Deserts before and was the first one caught in the general area since 2009.

Even more importantly, one team caught a plains mouse. Read more about this exciting find here (near the end of the article). This is the first time a plains mouse has been recorded in Sturt National Park.

These are positive signs for the Wild Deserts project.

Despite two record dry years, mammals that were once common here are returning of their own accord. Considering the project has only been running since 2016, the future looks bright.

If only the rain would fall.

On the other hand, such dry conditions have a few positive effects. Let me explain.

A Clean Slate

The record dry conditions made the job of clearing kangaroos from the exclosures relatively easy. Remember, kangaroos wouldn’t have naturally populated this arid region because no natural fresh water sources existed.

With the crippling drought and record heatwaves, thousands of kangaroos have died of starvation and thirst. By the time the exclosures where completed, virtually no kangaroos lived within them. The very few that did were carefully and humanely shepherded out of the exclosures.

The dry also gives ecologists a chance to record and observe the environment in (hopefully) the worst possible conditions.

For example, a group were collecting fungus samples to analyse soil fungus in these dry conditions. The fungus and plants work together. Fungus produces phosphates while the plants provide nutrients from transpiration. Mother Nature’s pretty clever!

So these “fungus detectives” will return every year and form a picture of how the fungus responds, as the country returns to its original state.

The other positive was in observing people’s reactions to the arid environment in which they found themselves. What do I mean by this? I’ll tell you a story…

A Fresh Perspective

Daniel and Bridget were from Wollongong and had studied ecology-related courses at UOW. Bridget had volunteered at Wild Deserts before and knew what to expect. Daniel on the other hand was different.

He’d never really been off the east coast. He’d grown up in Wollongong and hadn’t really seen much of this amazing country at all. So Daniel jumps in a car with Bridget and travels over 1,500km from one corner of NSW to the other.

Of course along the way he sees every type of environment you could imagine, including the bone dry Darling River and the feral goat-stripped landscape between Cobar and Broken Hill.

I have no doubt his senses were overwhelmed with the alien landscape on the other side of the windscreen.

Then he arrives at Wild Deserts and starts to see. I really enjoyed watching him transform from “oh my god, look at all this dirt” to “wow, this country is unbelievable”.

Daniel and I were with Reece on the third day. Reece and I described how this country comes alive after rain, how the grasses and flowers grab every bit of moisture and cling onto it like their survival depends on it… which it does.

We tried to paint a picture of an ecosystem bursting with life. For this is one of the miracles of the desert. All of the flora and fauna is so finely tuned to extracting every last piece of sustenance from such an arid landscape.

And to see this in action is something you never forget.

I could see Daniel processing all this… trying to imagine the cane grass swales filled with water, birds in every direction devouring all types of insects, and carpets of native plants furiously flowering, then dropping their seeds in preparation for the next rare rain event.

Peta and I have a saying. People either “get it” or they don’t.

The ones who don’t are the people who drive through the desert and say it’s boring and lifeless. The people who do get it notice the subtle changes in soil and vegetation, the gentle slopes that lead to barely discernible water courses, the bird life and so on.

By the time Daniel left Wild Deserts, he well and truly “got it”.

I just hope he gets to see this country in times of abundance. That way he’ll see the circle close, and fully understand how this country can be so unforgiving at times, yet so full of life and energy when times are good.

Daniel reminded me of how I had reacted the first time I encountered true desert country. At first it was overwhelming then slowly I began to understand, to see, to appreciate, to love this arid country.

And while I’m in the mood for story-telling, let me tell you about something that could only happen when a group of ecologists get together…

Bag It, Lucy

There we all were, sitting around the table after yet another of Vicki’s brilliant dinners. Everyone was pretty weary and content after a big feed of homemade lasagna and homemade bread (yum!). The conversation had trailed off into a comfortable silence.

Insects buzzed around the light above us, occasionally venturing too close to the light then dropping unceremoniously onto the table.

Suddenly Chloe sat up like she’d just circled the last bingo number on her card. “Look, a giant click beetle!”

Lucy sat upright and leant in to inspect Chloe’s exciting discovery. Then she wordlessly stood up and glided over to a box full of sample vials.

She selected a vial, Chloe picked up the unfortunate click beetle and dropped it in the vial. Lucy then screwed on the lid and placed it with the other invertebrate samples they had collected during the week.

Then Lucy sat down, Chloe slumped back into her food coma and all was silent again.

No one at the table had even noticed, apart from Peta and me.

Peta and I glanced at each other and burst out laughing. Chloe looked across the table with a quizzical expression. “Whaaa?” she enquired through her food-induced haze.

Now I’m not sure if collecting invertebrate specimens at the dinner table is considered normal behaviour in the ecology world, but we certainly hadn’t seen anything quite like it before. That could only happen at a table full of ecologists!

Speaking of ecologists. One thing this group had in common was a love of birds. Several were keen bird-watchers and had an encyclopaedic knowledge of birds.

Well, it turns out Peta and I saw a rare and elusive bird in Western Australia… one that most birders would gladly donate their limbs for just to get a glimpse of. That’s right, us who struggle to tell the difference between a magpie and a crow (well, maybe that’s a slight exaggeration) had seen Princess Parrots.

How To Break A Birder’s Heart Without Even Trying

This story begins with Simon. He was patiently showing us Bourke’s Parrots through his binoculars and teaching us where to see them in the wild, how to identify them, pointing out their call and so on.

You see, every day a flock of Bourke’s Parrots came in before dawn and after dusk to the small soak at Fort Grey. This was the same soak where we saw Simon had been holed up in his 4WD doing a bird survey when we first arrived.

They are beautiful birds, highly colourful and cheeky like most parrots are.

And we happened to be camped not 20 metres away from the soak. So we were in prime position to hear and see them every day.

Now somehow the subject of Princess Parrots arose. Neither of us had ever heard of them. Simon mentioned they were unusual because they had a long tail.

“Oh yeah, we saw them on the Gary Junction Road. I remember them because they were definitely parrots but they had a really long tail”, I said casually.

Simon paused in his measured way, not sure whether to believe me or not. I had no idea about the significance of what I’d just said. He asked a few more questions. Then he showed us a photo of one.

“Yep, that’s it”, Peta and I said.

Simon grinned slightly and raised his eyebrows. “They’re really rare and elusive you know. Very few people have actually seen one and very little is known about them.”

Now it was our turn to fall silent. We let this sink in for a while.

Cooool!

It was getting close to dinner time, so the three of us wandered up to the homestead. After dinner we were all having a bit of a yarn. Then Simon called out to Tom H. “Hey Tom. These guys saw Princess Parrots in WA”. A slight hush fell over the table. The birders were interested, very interested.

Tom H’s jaw dropped then his face turned to disbelief. He fired a few questions at Peta and me, which we apparently answered to his satisfaction. Once he was convinced we were telling the truth, Tom’s shoulders slumped.

We’d broken him, the poor bugger.

You could almost see him thinking, “What the hell? I’ve spent my life looking at birds. I know every species and sub-species known to mankind. Yet these two blow-ins drive right past Princess Parrots perched in a bush WITHOUT EVEN KNOWING WHAT THEY’RE LOOKING AT!!!”

Ah well, them’s the breaks…

To cap off a great week, we had a chance to see the floodwaters running down Cooper Creek at Innamincka. Sho had a couple of car issues, so she stayed an extra couple of days after everyone else left. We did too, we weren’t in any hurry to get anywhere.

A Quick Loop

So the three of us jumped in the truck and did a quick 500km return trip to Innamincka.

We had a ball.

Sho found some birds along the way and we introduced her to the sights of Innamincka. We watched the water flowing over the causeway and marvelled at how this live-giving water had come from so far away. There’s something pretty amazing about witnessing a dry flood.

On the trip back we were treated to a phenomenal display of desert colours in the late afternoon sunlight.

And to top off a perfect day, when we rolled back into Fort Grey Bec served up an amazing curry followed by a self-saucing pudding. Yum!

Wrapping Up

The Wild Deserts annual Ecological Survey was one of the best experiences we’ve ever had.

Don’t be fooled, it’s hard work. The days are long, the work is sometimes physically hard. And the heat can be pretty savage. But the people, the tiny creatures you find and the knowledge you acquire make up for the hard work ten times over.

We both learnt so much from such a diverse group of people, all incredibly knowledgeable about arid zones. Our brains were bursting with new knowledge by the end of the week.

Bec and Reece are special people. The buck stops with them, they’re the ones who put the ideas into practice, the ones who make it all happen. Their passion and enthusiasm is infectious.

A big thank you to Bec and Reece for the opportunity to be involved in the Wild Deserts project, even in such a small way.

We’ll be back, for sure!

Wild Deserts is on Wongkumara and Maljangata country.

FAQs

What is an Ecological Survey?

An Ecological Survey records detailed information about the plants and animals of an area. This gives Wild Deserts a yearly snapshot of what’s happening within and outside their project boundaries.

They use the data both to analyse the success of their programs and to make decisions based on facts.

Survey Areas are carefully selected, and multiple points are situated throughout (and outside of) the project area. For example:

- Inside exclosures,

- Within the Wild Training Zone,

- In the wider Sturt National Park, and

- Across the border in South Australia.

A typical Ecological Survey Area is set up as follows:

- A 100m x 100m zone is marked out and the corners are recorded by GPS. Belt transects (see below) are carried out along the perimeter.

- Within this zone are located pitfall traps, invertebrate traps and vegetation survey areas. See below for definitions.

Each Survey Area is studied and recorded annually to build a picture of what’s happening in each area. Wild Deserts use this information to:

- Figure out how successful their work is to date, and

- To determine what further work needs to be done.

What is a Pitfall Trap?

Pitfall traps consist of a series of holes lined up in a straight line, equally spaced over about 20 metres. PVC pipes (capped on the bottom) are sunk into the ground and act as the traps.

Then a low temporary fence is erected. The fence runs over the centre of each trap and corrals small creatures along the fence, until they fall into a pit. Then we come along, scoop them out carefully, record all their vital statistics then release them.

What is an Invertebrate Trap?

An invertebrate trap catches insects. A short PVC pipe is sunk into the ground, the top flush with ground level. Then you drop a plastic beer cup into the pipe, add some liquid to attract insects and drop a couple of sticks in to give wayward lizards somewhere to escape from the liquid if they fall in.

What is a Vegetation Survey?

Vegetation surveys are used to record the amount and type of vegetation in a given area. These are randomly placed within a belt transect zone at Wild Deserts. Small square areas are marked out and the vegetation within these areas is recorded.

By doing this, Wild Deserts get a year-on-year record of what vegetation is within the study zone.

What are Belt Transects?

Two people walk the perimeter of the Survey Area. One has a two metre long stick which they hold horizontally. As they walk, they call out whatever passes under the stick and the second person records it. For example they will record scats, holes, cracks and so on.

This gives Wild Deserts a record of the distribution of species within each Survey Area.

What is a Swale?

A swale is the land between two sand dunes.

Are marsupials only found in Australia?

No. Australian marsupials are perhaps the best known… kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, koalas and so on. And yes, Australia has the largest variety of marsupials world-wide. However, marsupials are also found in New Guinea and various sub-species of opossums inhabit the Americas.

Get your Traveller’s Guides

… and a whole lot more at our FREE RESOURCES Page!

Any questions or comments? Go to the Comments below or join us on Pinterest, Facebook or YouTube.

Any errors or omissions are mine alone.

For more NSW National Parks, go here.

You Guy’s are amazing, would love to be able to do this.

Lived in Tennant Ck for 16 years and just loved the natural environment of the outback.

Hi Denis, Thanks! You would have seen plenty of the beautiful outback around Tennant Creek. A great part of the world. Cheers, Andrew